‘I want to see the Lord. I have spent hours before Him in the Blessed Sacrament. … [N]ow I want to see Him face-to-face.’

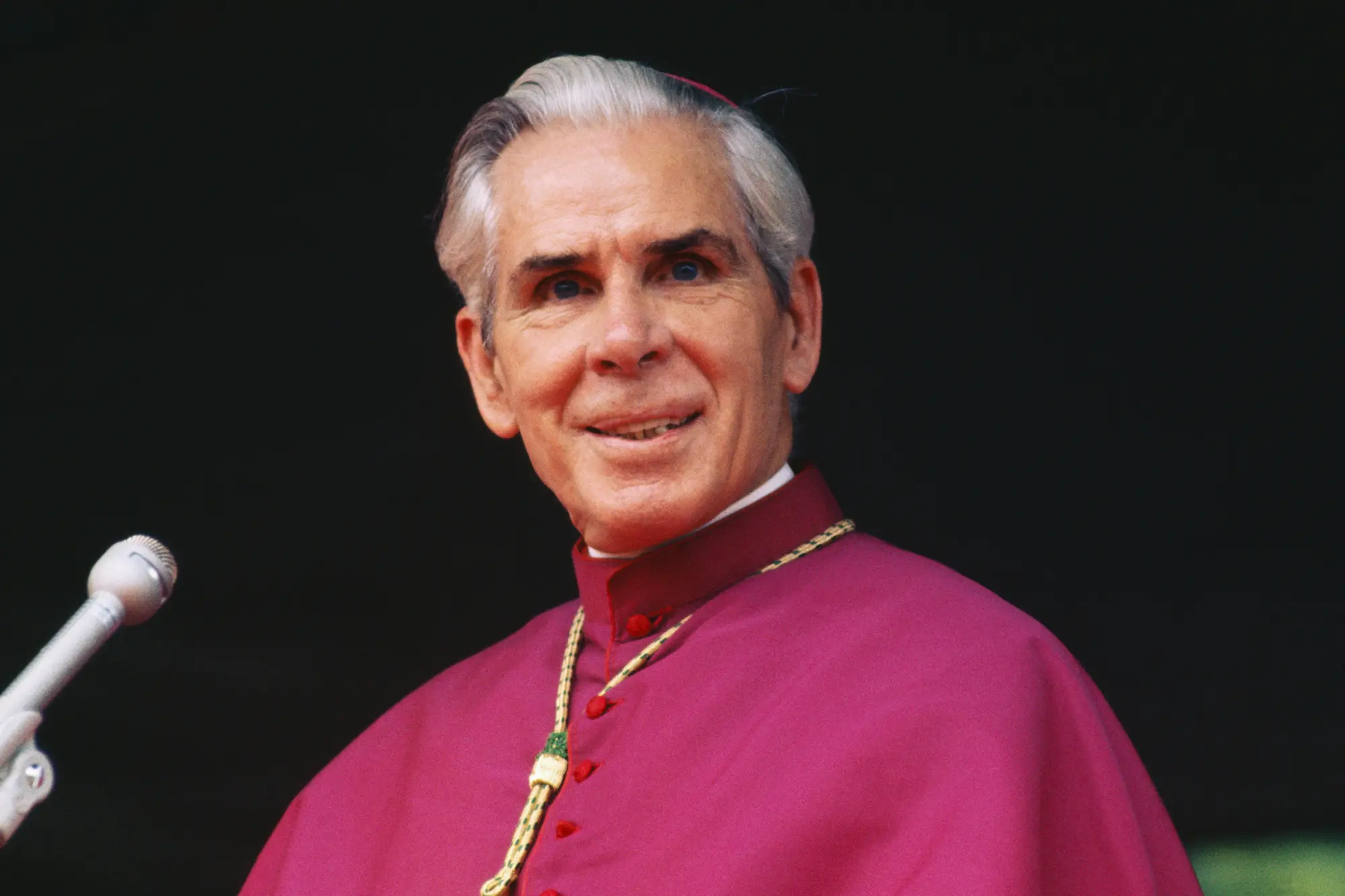

God lavished many gifts upon Venerable Archbishop Fulton Sheen, including a brilliant mind, a remarkable memory, a magnificent voice, and enviable oratorical skills. He transcended the parish and the diocese. He was, as Thomas Reeves stated in the title of his masterful biography, “America’s Bishop.”

Archbishop Sheen made is easy for Catholics to be openly proud of their faith and others to want to imitate it. The Italian phrase comes to mind: Natura il fence, poi rupee lo stampo (“Nature made him and then broke the mold”).

Would there ever be another Bishop Sheen? The Jesuit magazine America called him “the greatest evangelist in the history of the United States.” Another journalist remarked, “No Catholic bishop has burst upon the world with such power as Sheen wields since long before the Protestant Reformation.”

Despite his gifts and immense popularity, Archbishop Sheen always deflected praise. “I am only a porter who opens the door,” he said. “It is the Lord who walks in and does the carpentry and the masonry and the rebuilding on the inside.” He dismissed publicity, stating that it was “as artificial as rouge on the cheek. Doing the job is the important thing, even if you’re a street cleaner.”

Sheen frequently spoke of his death, much to the consternation of his friends.

“It is not that I do not love life; I do,” he would assure them. “It is just that I want to see the Lord. I have spent hours before Him in the Blessed Sacrament. I have spoken to Him in prayer, and about Him to everyone who would listen, and now I want to see Him face-to-face.”

In his chapel was a painting of Christ on the cross, done by Dr. Simon Stertzer, a cardiologist whom Archbishop Sheen credits with saving his life. In the painting, there is a concentration on Christ’s eyes that shows both pity and love. For the archbishop, the crucifix is not just something that happened but is something that continues to happen by everyone who commits a sin.

The second year after his open-heart surgery, Bishop Sheen was confined to his bed for many months due to overwork. During that time, he instructed four converts and validated two marriages. As he quipped, “The horizontal apostolate may sometimes be just as effective as the vertical.”

Overwork was the story of his life. His typical working day was 19 hours. In 1946 alone he was writing between 150 and 200 letters a day. In the early 1950s, his television show was generating between 15,000 and 25,000 letters per day. He answered as many as his working schedule allowed.

His demanding schedule, however, was his way of responding in gratitude for the gifts God bestowed on him. But “the greatest gift of all,” he confesses in his autobiography, “may be His summons to the Cross, where I found His continuing disclosure.”

On the morning of Dec. 9, a young couple was with Archbishop Sheen at Mass and listened as he practiced part of a Christmas homily he was to deliver at midnight Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. That same day he wrote a letter to a certain Ann O’Connor, thanking her for a blanket she sent.

“My heart must be elastic,” he wrote, “otherwise it would break in gratitude for you friendship and gifts during the year.”